54 Introduction to data preprocessing

🏢 Lab class

In Lab 8, we have had a closer look at PsychoPy output files. Now, it is time to start analysing these output files. This is where your statistics knowledge becomes relevant for the practicals: Using an example output file, today we will calculate means, medians and standard deviations (SDs).1

54.1 What SPSS needs and what we get from PsychoPy

Let’s assume your aim is to find out if RTs on incongruent flanker trials are on average significantly slower than RTs on congruent flanker trials. To investigate this, you would have participants complete a number of trials from both conditions and run an inferential statistical test on the data. Remember that this is a within-subject design, as the same participants complete all levels of the IV, so for a parametric analysis this inferential test would be a paired-samples t-test.

What SPSS needs: One row per participant.

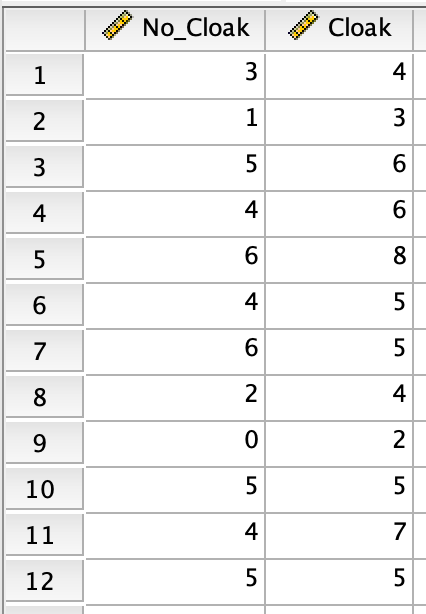

Think back to the data file for Statistics lecture 8 (“Comparing means - part 2”). In this file, one row corresponded to one participant, and for each participant you had two data points corresponding to the two conditions:

This type of file is what SPSS needs to run a paired-samples t-test: For a within-subjects design with two conditions, we need two data points for each participant, both in the same row.

Accordingly, for the flanker task you would need one data point for congruent trials and one data point for incongruent trials for each participant.

What we typically get from PsychoPy: Many rows per participant.

If your flanker task had, say, 72 experimental trials (half congruent, half incongruent), there would be 36 rows per condition in your PsychoPy output file! As SPSS expects one row per participant, we need a summary measure to represent the performance of each participant in both conditions (i.e., a mean or median). The remainder of this chapter and the next chapter explain one approach to obtaining this summary measure.

54.2 How to get from PsychoPy output to SPSS input

The simplest approach for creating our summary measure would be to simply calculate the mean RT for all trials from a condition and participant. However, this approach has the potential shortcomings listed below.

Extreme RTs

First, there might be extremely fast as well as extremely slow responses. Extremely fast responses (say, faster than 100-150 ms) are likely anticipatory responses. That is, participants anticipated the appearance of the stimulus and pressed a response key before properly processing the stimulus.

Why 100-150 ms? The reason for this is that even in the macaque it takes about 70 ms on average for signals from the retina to arrive at the primary visual cortex (Lamme & Roelfsema, 2000). In a choice reaction time task, once these signals arrive, lower and higher order visual processing areas must process the object identity (“Which target is it?”). Once the target has been identified, the correct response must be identified (e.g., “H requires a left-hand response”). Finally, a motor signal must be sent to an effector (i.e., a finger must press down one of the response keys).

This is not to say that all of these processes occur strictly sequentially, but taking the various processing steps into account, it seems extremely unlikely that participants can produce valid responses (not just lucky guesses) before 100-150 ms (also see Whelan, 2008).

On the other hand, there might be extremely slow responses. These are likely due to lapses of attention or external distractions. Or, if your trials have infinite length, a participant might also have taken a break in the middle of your experiment! As these slow responses are not a direct consequence of the processing requirements of the task, an argument can be made for excluding them as well. The exact cut-off will be different for different tasks. For a straightforward flanker task run with healthy young participants, RTs which are longer than, say, 3 seconds might be considered extreme RTs.

Incorrect RTs

In addition, including error trials would bias our measure of central tendency:

- There is strong evidence that error trials in speeded reaction time tasks are faster than correct trials (e.g., Smith & Brewer, 1995).

- Errors also occur more frequently on incongruent trials than on congruent trials (e.g., Derrfuss et al., 2021).

Including error trials would underestimate mean RTs because errors are typically fast. This effect would be disproportionately large for incongruent trials, where errors are more common.

As a result, including RTs from incorrect trials would reduce the interference effect, making it less likely to detect a significant difference.2

Outlier RTs

Finally, there may be outliers. In the HHG framework, extreme RTs are defined in absolute terms, whereas outlier RTs are relative to other RTs within the same condition for the same participant.3

There are several ways to identify and reject outliers: based on standard deviation, interquartile range, absolute median deviation, or by trimming (i.e., removing a fixed percentage of trials—e.g., the fastest and slowest 20%).

For our lab classes, we will focus on SD-based outlier rejection—a pragmatic choice. This method has a drawback: outliers inflate the SD, so extreme values can mask other outliers. However, SDs are easy to compute and sufficient for illustrating the concept. Moreover, a recent study (Berger & Kiefer, 2021) suggests that SD-based methods are relatively unbiased. That said, this conclusion is based on simulated data, and it remains unclear how well those simulations reflect real-world outliers. Furthermore, another study argues that outlier rejection may sometimes do more harm than good (Miller, 2023).

In short, the topic is still debated. Our goal is to ensure you understand how to apply SD-based outlier rejection so you can use it when appropriate.

References

If you can’t remember how exactly these measures of central tendency and dispersion are calculated, you might want to return to your statistics lectures and look this up.↩︎

In fact, we recently showed that a very similar issue has been a confound in many publications investigating post-error slowing (Derrfuss et al., 2021).↩︎

Note that these terms are used inconsistently across the literature, so always define them explicitly.↩︎