13 Psychological research basics

“A deeper understanding of judgements and choices also requires a richer vocabulary than is available in everyday language.”

— Daniel Kahneman, Thinking, Fast and Slow

→ Studying psychology is in some ways like learning a new language. You need to acquire a vocabulary for expressing psychological facts and ideas. In some cases, this will require learning new terms. In other cases, this will require understanding the specific meaning of more common terms in a psychological context (e.g., significant, reliable, valid).

“Die Grenzen meiner Sprache bedeuten die Grenzen meiner Welt.”

(“The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.”)— Ludwig Wittgenstein, Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus

→ Without mastering this vocabulary, your ability to grasp psychology as a scientific discipline will remain limited.

“Extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence.”

— Carl Sagan, Broca’s Brain

→ In psychology, as in other sciences, bold or surprising hypotheses demand strong empirical support. The more a claim challenges established knowledge, the more rigorous the evidence must be before it can be considered credible.

“Habe Mut dich deines eigenen Verstandes zu bedienen.”

(“Have the courage to use your own reason.”)— Immanuel Kant, What Is Enlightenment?

→ Kant argues that true progress, for both individuals and society, only happens when people stop blindly following authority and start thinking for themselves. It’s a challenge to question what you’re told and form your own conclusions, rather than passively accepting information from others. This intellectual courage is the foundation of all critical thinking and true learning.

🏢 Lab class

In this lab, we will cover issues related to Chapters 1 to 3 and 5 in Beth Morling’s book. The first three chapters in Beth’s book are an introduction to scientific reasoning and Chapter 5 focuses on identifying good measurement. Please note that your knowledge of these chapters will be tested in a summative quiz (see Chapter 15).

Some of the key concepts covered in Chapters 1 to 3 and 5 are:

Empiricism

Psychological reasoning must be based on data, not opinions or intuitions.

Measured and manipulated variables

A measured variable is one whose levels (the different values or categories it can take) occur naturally and are simply observed and recorded by the researcher.

A manipulated variable is one whose levels (e.g., experimental conditions such as training vs. no training) are controlled by the researcher. True experiments are based on manipulated variables (the term true is sometimes added to distinguish them from quasi-experiments, which do not involve manipulation).

Some variables can only be measured (e.g., height or intelligence), whereas others could be measured or manipulated. If, say, you are interested in the effect of caffeine consumption on exam performance, you could ask participants how much coffee they drank before the exam (measured) or you could assign them to different levels of caffeine intake before the exam (manipulated).

Conceptual and operational definitions

A conceptual definition is a general explanation of what the concept means, based on theory or scholarly definitions. For example, Neisser et al. (1996) proposed the following conceptual definition of intelligence: “[Intelligence is the] ability to understand complex ideas, to adapt effectively to the environment, to learn from experience, to engage in various forms of reasoning, to overcome obstacles by taking thought.” (Neisser et al., 1996, p. 77)

An operational definition on the other hand describes how to measure or observe a concept. They describe what you need to do (i.e., which operations to perform) to measure or observe something.

Types of claims

There are three prototypical types of claims that can be made in the context of psychological studies:

- Frequency claims: The aim is to measure a single variable as accurately as possible. Example: “39% of teens admit to texting while driving.”

- Association claims: Investigate associations or correlations between variables. Example: “Coffee consumption linked to lower depression in women.”

- Causal claims: Claim that one variable (the independent variable or IV) causally influences another (the dependent variable or DV). Causal claims can only be based on true experiments. Example: “Spatial working memory training improves navigation skills.”

Reliability and validity

Two key concepts for evaluating psychological research are reliability and validity.

Reliability refers to how consistent a certain measurement is.

Validity refers to how well it measures what it is supposed to measure.

A good way to illustrate this is with scales. Imagine you weigh a 1 kg bag of flour on your kitchen scales ten times:

- If you get 10 different weights, the scales are not reliable. They are also not valid, because a measure that is not reliable cannot be valid.

- If the scales show 800 g every time, the measurement is reliable (because it’s consistent) but not valid (because the true weight is 1 kg).

- Only if you get 1 kg each time is the measurement both reliable and valid.

🏠 Self-study

If you took A-level psychology, some of the content in Chapters 1-3 and 5 in Beth’s book might sound familiar. Nevertheless, we would encourage to carefully read these chapters and compare their content to what you were told in school. Check if there are things you hadn’t heard about before. Ask yourself if what you read is consistent with what you previously learnt.

13.1 Empiricism

An important point made in Chapter 1 of Beth’s book is that psychologists are empiricists. We have pointed out above that psychological reasoning must be based on data, not opinions or intuitions.

Just to be clear: There is nothing wrong with opinions or intuitions. On the contrary. However, they can only ever be the beginning, but not the endpoint of psychological thinking. We need to test our opinions and intuitions empirically, that is, by conducting studies that generate data.

As an empiricist, you should not naïvely accept claims, but critically question them. Below are some key questions you could ask when encountering a claim.

- What does this claim actually mean?

- Given what you already know, how credible is the claim?

- What evidence is there to support the claim?

If there appears to be evidence to support the claim:

- Is the explanation provided plausible? What could be alternative explanations for the effect? E.g., does the study have methodological shortcomings?

- Is the effect statistically significant?

- How big is the effect size?

13.2 Conceptual and operational definitions

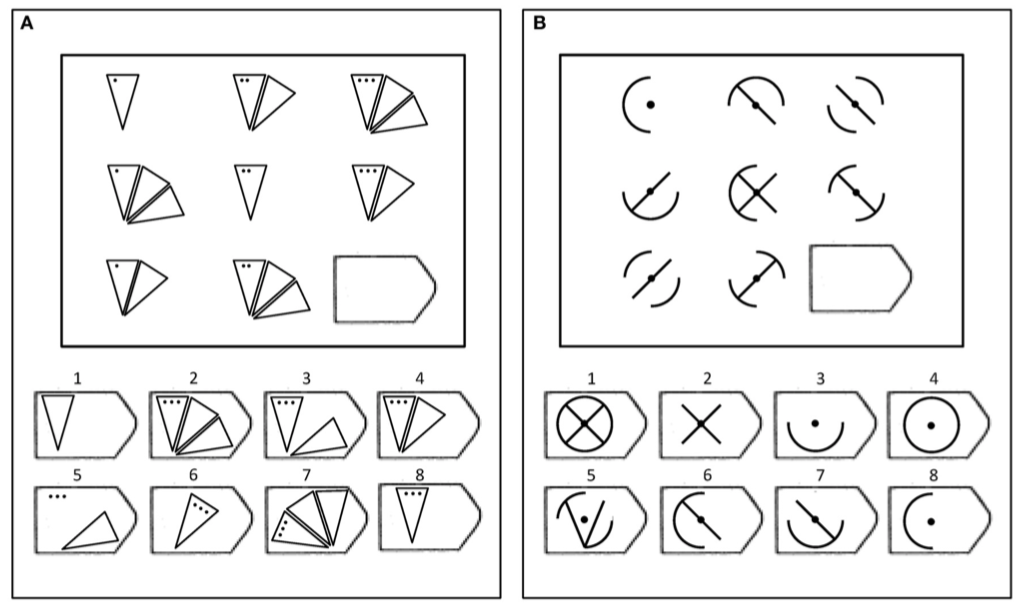

When it comes to measuring intelligence, various operational definitions have been suggested. One example is Raven’s Progressive Matrices:

Here the operational definition involves presenting participants with complex patterns they have to complete. Working out the correct answer arguably involves reasoning and problem solving. Whether or not this is indeed an appropriate way to measure intelligence is a matter of validity (see below).

Note that conceptual and operational definitions are not independent. If, for example, your conceptual definition of intelligence suggests that visuospatial and verbal abilities are separable, your operational definition of intelligence must reflect this distinction. That is, your test must include items that are assumed to measure visuospatial abilities and items that are assumed to measure verbal abilities.

Operationalisation can take rather different forms, each with their own advantages and drawbacks. Imagine you wanted to investigate the frequency of texting while driving (your conceptual variable). You could simply ask people how often they text and drive. These data would be simple to collect, but might suffer from social desirability bias. Alternatively, you could hire research assistants to directly observe drivers in their cars. This would likely give you a better idea of the actual texting frequency in cars, but would be a very time-consuming and costly way of collecting the data. Finally, you could ask people how often their friends text and drive. You might hope that this approach removes some of the social desirability bias, while at the same time making the data easy to collect.

13.3 Types of claims

Note: The type of data determines the type of claim you can make:

Measured variables → Association claims

If you asked participants how much coffee they drank before the exam and found that those who drank more coffee performed better, you could make an association claim: “Caffeine intake is associated with better exam performance.”

Why is a causal claim not possible? The association between coffee intake and better exam performance might not be due to the coffee intake per se, but could be explained by a third, unmeasured variable: For example, the association between drinking coffee before an exam and better performance could be explained by personal organisation and time management skills.

- The Well-Organised Student: This student likely has their study schedule managed, their materials prepared, and their morning routine planned. Because they aren’t rushing or panicking, they have ample time for a normal morning routine, which may include making and drinking a cup of coffee.

- The Less-Organised Student: This student might have crammed the night before, overslept, and is now rushing to get to the exam on time. In their haste, they skip breakfast and have no time to make coffee.

In this scenario, the coffee isn’t causing the better performance. Instead, the ability to have time for coffee is simply a marker of a well-organised student. It’s the underlying organisational skills which lead to better study habits and a less stressful exam day experience that is the true cause of the better performance.

Manipulated variables → Causal claims

If you randomly assigned participants to two groups (caffeine vs. placebo), controlled their caffeine intake, and found that those in the caffeine group performed better, you could make a causal claim: “Caffeine intake leads to better exam performance” (at least under the specific conditions you tested)

Note that the coffee example is a made-up one to illustrate the difference between claims based on measured and manipulated variables. If you’re interested in the actual effects of caffeine on cognition, check out these studies: James (2014), McLellan et al. (2016), Ramirez de la Cruz et al. (2024), Ricupero & Ritter (2024)

13.4 Reliability and validity

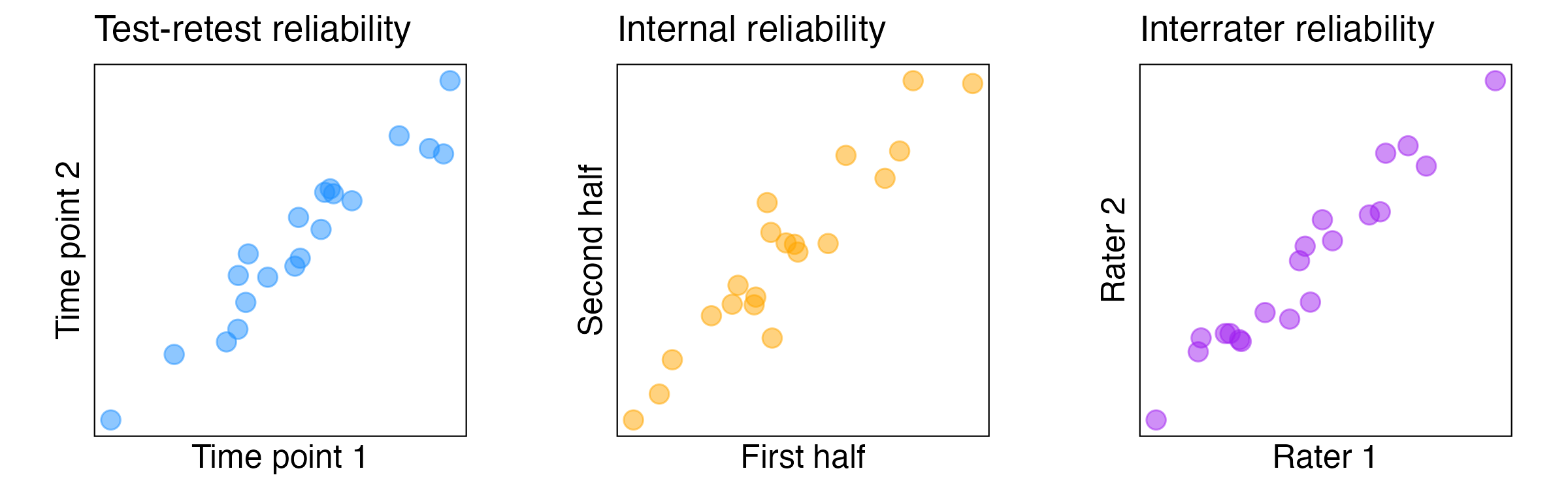

Reliability can be measured in the following ways:

- Test-retest reliability: Can be used for experimental or questionnaire studies. The basic idea is to repeat the study after a delay with the same participants and to investigate how similar the participants performed on both attempts.

- Internal reliability/consistency: Typically used for questionnaires. The basic idea here is to split a questionnaire into different parts (e.g., two halves) and to investigate how well these parts correlate with each other.

- Interrater reliability: Typically used where independent observers rate certain behaviours. The idea is to investigate how similar the ratings across observers are.

Note that all types of reliability predict a high positive correlation if measurements are reliable:

In Chapter 3, Beth refers to four “big validities”:

- Construct validity: How well has the researcher defined and measured (frequency and association claims) or manipulated (causal claims) the variables of interest? Does the test correlate with other tests that measure related constructs? (→ convergent validity) Does the test not correlate with tests that measure unrelated constructs? (→ discriminant validity)

- Statistical validity: How precise is our estimate and how big is the effect size?

- External validity: How well do the results generalise to different people, times and places?

- Internal validity: To what degree can we be sure that there are no alternative explanations for the results? (relevant for causal claims)

As the scales example above shows, reliability is necessary but not sufficient for validity.

It is necessary because a highly unreliable test cannot be valid. In fact, a test’s reliability sets the upper limit for its validity. That is, a test cannot be more valid than it is reliable.

Why? The highest possible correlation a test can have is with itself (which is a measure of reliability—test-retest reliability). No other test can correlate more strongly with a test than the test itself (and correlations with other tests are a measure of validity—convergent validity).

However, reliability is not sufficient, as shown by the scales example: Even a highly reliable measurement is not necessarily valid.

13.5 Confirmation

Please confirm you have worked through this chapter by submitting the corresponding chapter completion form on Moodle.