34 Beyond the single trial

🏢 Lab class

This week, you will learn how to present multiple trials in PsychoPy using loops and conditions files. Our previous exercises focused on running a single trial. However, in a typical experiment, we have of course more than one trial. In theory, we could define a new routine for every individual trial:

However, given that experiments can include hundreds of trials, it would be extremely time-consuming and laborious to set up such an experiment. This is where loops come in: A loop repeats one or more routines a specified number of times. In this example, the loop trials repeats the routine trial:

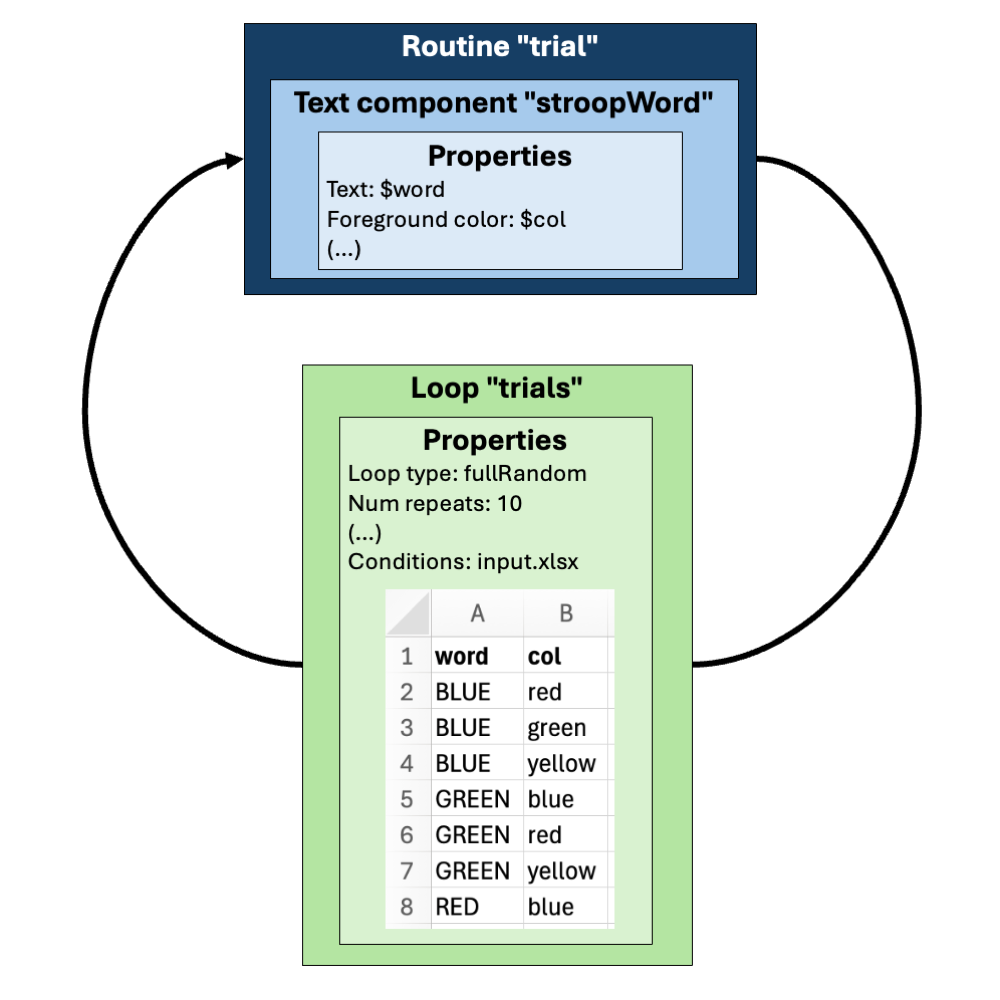

Most importantly, when repeating routines in a loop, you can update component properties (e.g., stimulus size, colour, position) from one trial to the next. The information on how to update the component properties comes from a conditions file attached to the loop. Using a Stroop trial as an example, you can think about the relationship between conditions files, loops and modifiable component properties in the following way:

In this example, the routine trial has a Text component stroopWord that has properties (the text displayed and the text colour) that are variable (indicated by the $-sign—more about this later). The loop with its attached conditions file has the information on how these component properties should be changed from trial to trial (i.e., which word should be presented and what colour it should be presented in).

One of the most frequent errors made by PsychoPy beginners is this: If you want to change a component property (a piece of text, an image,…) in a routine from one trial to the next, this property can’t be fixed. It must be defined using a variable.

If, for example, you want to present one image on the screen and change this image from one trial to the next, you can’t set up the image component using a particular image (i.e., using a file name such as cat.png).

You also can’t use two image components in the same routine, one presenting cat.png and the other presenting dog.png. Using two image components in the same routine would always present both images. However, on any given trial, you just want one image.

Therefore, the image must be a variable (e.g., $img).