Chapter 2 PSGY1001: Key facts

2.1 Lecturers and demonstrators

Jan Derrfuss (Module Convenor)

Jan is a cognitive neuroscientist from Bamberg, Germany. He initially studied architecture in Dresden, quit after a year, then did an internship at the Cotswold Community in Ashton Keynes, Wiltshire, before returning to Germany to study psychology in Landau in der Pfalz. He completed his PhD at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences in Leipzig and has been working at the University of Nottingham since 2013. His main research interests are cognitive control, working memory, and performance monitoring.

Jonathan Stirk

Jonathan is a cognitive psychologist with interests in attention and emotion. He studied Combined Science (Psychology/Biology) at Leicester University, and after a period as a research assistant examining aspects of game theory, he completed a PhD looking at how virtual reality could be used to investigate spatial cognition. He has been an assistant professor at Nottingham for over 15 years!

The demonstrators

Demonstrators are PhD students in the School of Psychology. Together with the lecturers, demonstrators will answer your questions, give you feedback and mark your work. This year’s demonstrators are:

- Beth Huntington

- Connor McGee (from 15/11/21)

- Elliot Howley

- Josh Khoo

- Karl Miller

- Kirsten Williams

- Meryem Yasdiman (until 05/11/21)

- Nick Simonsen

- Victoria Newell (from 15/11/21)

- Yalige Ba

You can find contact information for lecturers and demonstrators on Moodle in the section “Contact the lecturers and demonstrators”.

2.2 Module content

This module focuses on key competencies for empirical research. Lab 1 focuses on a number of preliminaries: getting access to the book we will use for this module, setting up your computer, working out how to use Moodle forums and choosing a note-taking app.

The remainder of the module is going to follow a prototypical research process: We will start with questions relating to psychological research in general and experimental design in particular (Labs 2-4), then we will move on to implementing experiments using computer software (Labs 5-8), we will conduct data analyses next (Labs 9-14) and finally we are going to focus on how to write a study up (Labs 15-20). The next paragraphs describe these steps in more detail.

Labs 2 to 4 are an introduction to scientific thinking in psychology, ethical principles in psychological research and experimental design. This includes criteria that characterise good research (e.g., reliability and validity) and problems that might occur when conducting an experiment (e.g., the presence of confounds or ceiling effects).

Labs 5 to 8 will focus on learning how to use PsychoPy, a piece of software developed here at The University of Nottingham that we will use to present stimuli (e.g., text or pictures) on a computer monitor and to record responses using a keyboard.

Labs 9 and 10 will focus on data preprocessing. In an experiment, a participant will typically respond multiple times to the same experimental condition. This is done to increase the reliability of the measurement. When we preprocess the data, we typically exclude incorrect trials and reject trials with unusually fast or slow response times (RTs). Once this has been done, we average individual RTs on a per-condition basis (alternatively, we might decide to compute medians). In addition, we usually also compute accuracies or error rates.

Once we have the mean RTs and accuracies for each participant, we can calculate statistical measures for a group of participants. This will be the focus of Labs 11 and 12. We will look at missing data, data cleaning, outliers and summary measures such as the mean and the standard deviation.

Labs 13 and 14 will focus on inferential statistics. For example, we will ask if an RT difference between two conditions is actually statistically significant (i.e., very unlikely to occur by chance). In our labs, we will focus on t-tests and correlation tests.

Labs 15 to 20 will focus on writing lab reports. When you write a lab report, you will need to bring together the skills learnt in all the previous labs: You will need to understand an experiment implemented in PsychoPy, you will need to describe the design of the experiment in the Method section of the lab report, you will need to include descriptive and inferential statistics in the Results section, and you will need your knowledge about research and experimental design to critically analyse your own research as well as the research done by others in the Introduction and the Discussion sections.

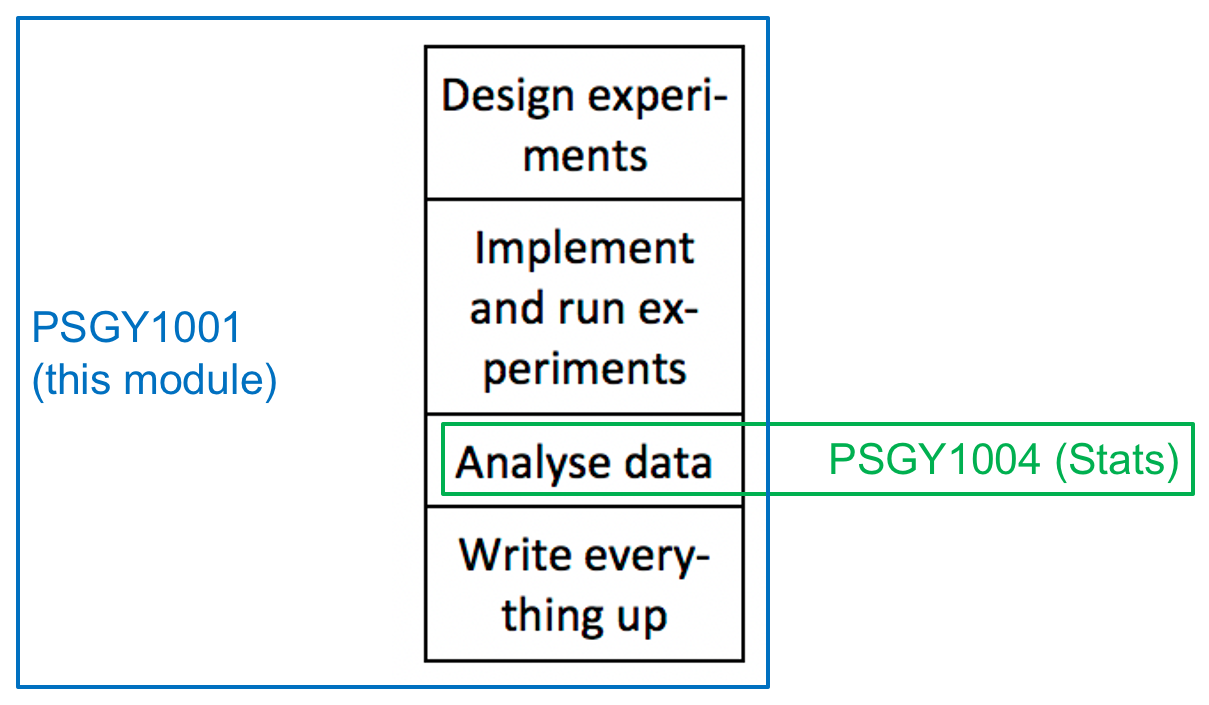

PSGY1001 is related to PSGY1004, but has a much broader focus as shown in Figure 2.1.

Figure 2.1: A comparison of PSGY1001 (Practical Methods and Seminars) and PSGY1004 (Statistical Methods).

You can find a brief semester overview in table form (including when assessments are set and due) in Appendix A.

2.3 Workload

Each week, you should work through the newly released material on the Hitchhiker’s Guide and, where applicable, read the accompanying chapters in Beth Morling’s book. The timetable suggests that you do this on Monday afternoons. However, you can review the materials whenever you like, as long as it is before the in-person session (see Section 2.4.1).

You must also attend the lab meetings on Thursdays or Fridays (depending on the group you are in; see Section 2.4.1). In addition, there will usually be activities, assignments or quizzes to complete each week. You must make sure to submit assignments before the deadline.

So, how much time per week should you spend working on PSGY1001? It is of course difficult to give a general answer to this question, but we thought we will give you an idea of the time the University expects you to work for this module. The University assumes that 1 credit translates into approximately 10 hours of effort. Thus, for a 20-credit module like PSGY1001, you would be expected to put in roughly 200 hours of effort. The whole academic year has about 36 weeks. Thus, as a very rough estimate, you would be expected to spend around 5 1/2 hours per week working on PSGY1001.

2.4 In-person and online support

We’re sure you’ll have many questions. Please don’t hesitate to ask them! We will either answer your question straight away or give you hints on how to find an answer. When we give hints, we do so to support you in learning how to solve problems in an academic context, which will be a fundamental skill for your course. For example, we might ask you to approach a problem from a different angle or to do some further reading/online research. If you’re still stuck after an initial answer, just let us know and we’ll help a bit more. You can ask as many questions as you would like to! To ask a question, please use one of the options listed below.

2.4.1 The lab meetings

We will have weekly 45-minute lab meetings on Thursdays or Fridays. The lab meetings are an opportunity to ask questions and get help in person. The meetings will take place in room A20/21 or A5 in the Psychology building. These rooms are equipped with iMacs. Thus, it is not required that you bring your own laptop to these meetings. However, you can bring your own laptop if you would like to.

Please observe the coronavirus safety guidance. If you do need to miss a session, you will be able to catch up.

All first year psychology students have been allocated to a lab group. Your group membership determines when and where your lab meeting takes place. Lab meeting attendance is compulsory.

Please download the file with group allocations to find out which group you have been allocated to and when and where your lab meeting takes place. The file is sorted by first name, then last name. (Updated 05/10/21)

Hopefully, this information will also be displayed correctly in your online timetable, but you might want to check the Excel file to be on the safe side. If your online timetable and the file do not agree, assume that the file is correct and the timetable is incorrect.

Please note that you can not usually change your group. However, under exceptional circumstances, we may allow students to switch groups. Note that you can only change to another group if there is someone in that group who is prepared to switch groups with you, or if someone has dropped out of the course. The reason for this is that the computer rooms will be fully occupied and that there will be no space for additional students. Students can change their group only once and only at the beginning of Semester 1, and changes need to be authorised by the module convenor. Please note that we reserve the right to decline your request to change groups.

2.4.2 The help desk

Help desks will take place on Wednesdays from 1-2pm in room A5 in weeks with lab meetings (i.e., there will be no help desk in the careers week). Help desks are run by a demonstrator. You can simply drop in if you have questions and don’t have to make an appointment in advance.

2.4.3 The Moodle page and forum

Here is a link to the Moodle page for PSGY1001. On the Moodle page, you will find links to all quizzes and assignments. In addition, you can access the module’s forums on the Moodle page. Here is a direct link to the PSGY1001 General forum. You can post on the forum at any time. We aim to respond within one working day. You can find more information on how to use Moodle forums in Section 4.3.

Please also use the forum to communicate with each other. If you can answer someone’s question please do so—an answer from a peer can be quicker and more helpful than an answer from a lecturer!

2.4.4 E-mail and personal Teams chat

The forum and the PSGY1001 chat are the preferred way to ask questions as all students can benefit from the answers given. However, sometimes you might want to bring personal issues to our attention that are not appropriate for posting on the forum. In such cases, please do send us an e-mail, chat with us on Teams or come to our offices. You can find our contact details on the PSGY1001 Moodle page in the section “Contact the lecturers and demonstrators”.

2.4.5 IT support

If you have any IT problems (e.g., difficulties to install a particular piece of software or to access one of the university’s online services), please contact IT services.

2.5 Assessment

As mentioned above, PSGY1001 focuses on competencies. Competencies include knowledge and skills, and both will be taught and assessed in PSGY1001. The module will be assessed continuously throughout the academic year. In our view, there is one major advantage to this form of assessment: If you don’t do well in one or even a few of the assessments, you can still get a really good mark overall. We feel that this approach is generally preferable to an approach that places all the emphasis on one single exam. Table 2.1 gives an overview of the different forms of assessment.

| Assessment.Type | Weight | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Coursework | 10 | Moodle quizzes (average of 3 quizzes) |

| Coursework | 10 | Create PsychoPy experiment |

| Coursework | 10 | Analyse data using Excel and SPSS |

| Participation | 10 | Research participation |

| Exam | 30 | Rogo exam in January |

| Lab report | 30 | Lab report based on lab report template |

To calculate overall marks, weights will be taken into account. Let us assume you had the following individual marks:

- Quizzes: 62, 65, 78 → average: 68.33

- PsychoPy experiment: 68

- Data analysis: 65

- Research participation: 100 (see RPS section below for details)

- Rogo exam: 72

- Lab report: 68

Your final mark would then be calculated as:

\[\frac{68.33+68+65+100+3\times72+3\times68}{10} \approx 72\]

Thus, your overall mark would be 72.

2.5.1 The Rogo exam

Please see Jonathan’s Moodle post for general guidance on Rogo exams.

With regard to the PSGY1001 Rogo exam:

- Up to 60 questions in 60 minutes.

- 4-alternative multiple choice questions, with no penalty for incorrect answers.

- About 75% of the question will be on research methods, specifically Chapters 1, 2, 3, 5, 10 and 11 (but not 4) in Beth’s book.

- Questions will be similar to Moodle quiz questions.

- About 25% of the questions will be on PsychoPy.

- Most PsychoPy questions will have the following format: screenshot of a flow, routine, component or input file together with a short description, followed by the question whether what is displayed will work or not (and if not, why not).

Note that we will release a 30-question practice quiz before the Christmas break.

2.6 Research participation scheme (RPS)

Participation in the scheme is managed via SONA which all 1st-year students are automatically registered on soon after the start of term. For further information on using the system, please refer to RPS section on the Moodle Psychology Homepage.

The RPS enables students to familiarise themselves with some of the research methods used in the School. Your SONA credits will be multiplied by 10 to calculate your RPS mark (thus, obtaining 10 points on SONA will result in a 100% mark). The deadline for taking part in experiments counting towards the RPS is the 30th of April. We would recommend to collect your 10 points as early as possible as it will get harder to find suitable studies once the deadline approaches.

If for some reason you cannot take part in the RPS, an alternative form of assessment is available. You may instead opt to complete a coursework element (also counting 10% of the module) instead. If you decide to opt out, then you must contact the module convenor before the 30th of November to obtain the details for the coursework and the submission deadline date.

2.7 Disability support and accessibility

If you are disabled under the Equality Act 2010 (this includes mental health difficulties, specific learning differences, or long-term medical conditions), you should contact the university’s Support Team who can develop a Support Plan with recommendations for reasonable adjustments to assessments for you.

We hope that by publishing the main module content as HTML pages it will be more easily accessible to vision-impaired students. If you have any suggestions on how to improve the accessibility further, please send me an email.

2.8 Extenuating circumstances

2.8.1 Summative assignments

If you are unable to submit a piece of assessment (e.g., due to illness) that is summatively marked (i.e., the mark does contribute to your overall module mark), you must submit an extenuating circumstances (EC) form before the deadline. (Please note that this is different for exams, where you can make an EC claim up to seven days after the exam.) You can find more information about ECs on the Student Services EC page and on the Student’s Union EC page.

2.8.2 Formative assignments

If you cannot submit a piece of assessment that is formative (i.e., that does not contribute to your overall module mark), you do not have to submit an EC form. As formative assignments do not contribute to your overall module mark, not submitting a formative assignment cannot incur a penalty. However, if you were unable to submit your formative assignment by the deadline (e.g., due to illness) and you would still like to submit your assignment after the deadline, you will need to make an EC claim. Update 27/10/21: Due to the high number of EC claims, the EC panel has decided that it will no longer be possible to claim ECs for formative assignments. If you miss the deadline, you will not be able to submit.

2.9 School vs uni

To conclude this chapter, we thought we’ll provide you with a—perhaps in places slightly provocative—comparison of what was expected of you in school and what will be expected of you at university:

| School | Uni |

|---|---|

| There are right answers and wrong answers. | Often, there is no right or wrong. There is well argued and less well argued. There is better evidence and not so good evidence. |

| You learn facts. | You should still learn facts, but also know how to find new facts and how to solve problems. |

| Knowledge is fixed. | Knowledge progresses. |

| The teacher knows, you learn. | Everyone learns (including lecturers). Also, students should learn from each other by discussing material covered in class. |

| There’s one textbook to read and it tells you the one and only truth. | There are lots of sources of information (this includes textbooks, but also research articles published in journals). There is no universal truth. |

| No one expects you to be interested in learning. After all, you didn’t choose to be there. | We expect you to be interested in learning. After all, you chose to be here. |

| No one expects you to really think. | We expect you to really think. If your head doesn’t hurt (metaphorically speaking of course), it’s not thinking. |

| Knowing how to use a smartphone is sufficient. | You need a computer and you really need to know how to use it. |

| Reading what the teacher suggests is sufficient. | You should do your own reading beyond the core material. |